Estonian Architecture Review MAJA article award 2019

But Why?

Siim Tuksam

Originally published in Estonian Architecture Review MAJA no 94 (summer/fall 2018)

The translation of human thinking and machine thinking in architectural design is ambiguous, their mediation requires the architect to ask the questions “How come?” and “What for?” over and over again in the process.

In his recent book, philosopher Daniel C. Dennett describes the development of consciousness in the course of evolution, asking the question “Why?”. It is a polysemantic question. We should differentiate between two whys: how come? and what for? In case of general existence, everyone has their own answer and nobody minds if you think that there is some kind of a metaphysical reason for being, or there is no reason whatsoever. It is certainly also possible to develop a logical argument that we are the result of evolution and thus our natural aim is to survive, to save the species. In architecture, however, you need a good answer to explain why you create a certain kind of space, as projects are often entangled with public interest. In terms of experiencing architecture, we may ask why the built environment is what it is. The given question could be further divided into two: typology and tectonics. In other words, how the space is organised and what it is made of. The former might play a more considerable role in organising our daily life, however, in terms of the art of construction, I find the question of tectonics far more exciting and complex. Why do buildings look the way they do? Where does their form come from, their geometry? In providing a framework for my study, I first attempt to consider how and where we have arrived (how come?) and then what to do with it (what for?).

How come?

Historians of architecture may study their objects from a great distance and make generalisations as to why and for what reason architecture developed into its present form. Vitruvius also described the development of architecture in terms of evolution: people began to construct shelters by gathering green branches or digging caves by imitating swallows, building with mud and twigs.

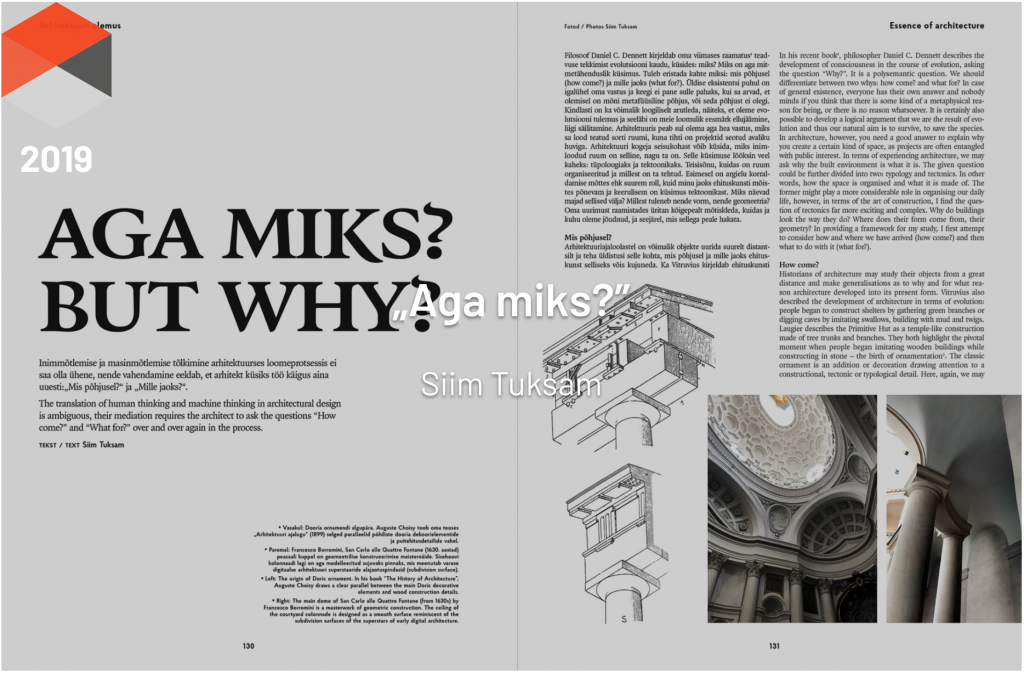

Auguste Choisy, the origin of Doric ornaments, from The History of Architecture.

A clear parallel between wooden construction and stone decor.

Laugier describes the Primitive Hut as a temple-like construction made of tree trunks and branches. They both highlight the pivotal moment when people began imitating wooden buildings while constructing in stone – the birth of ornamentation. The classic ornament is an addition or decoration drawing attention to a constructional, tectonic or typological detail. Here, again, we may draw a parallel with Dennett’s conception of consciousness’ need for continuity from the psychological point of view. This is what upholds culture and traditions and makes people imitate their previous experience. Dennett calls it Cartesian gravity.

Ornamentation reached its peak during the Baroque era when overflowing ornaments featured not only on buildings but also in the surrounding gardens. This was also the time of the Scientific Revolution. The birth of contemporary, modern architecture. The first industrial revolution gave rise to overcrowded cities – a gap emerged between man and nature which continued to widen until the rise of Modernism and Futurism in early 20th century. The world view became mechanical. Futurists hailed machines and war. Modernist art and literature introduce existentialism into laypeople’s ontology.

With Turing, the next and most influential step in people’s alienation from the comprehension of the world is taken in the middle of the previous century – the theoretical basis of artificial intelligence. Also the protagonists of digital architecture – the CNC or computer numerical controlled milling machines and 6-axis industrial robots – date back to the height of that era of cybernetics. There was new hope for understanding the world through computational technology, however, at the time, cybernetics came to fail completely bringing the studies of artificial intelligence to a standstill for a long time. In early 1990s, computers found their way into people’s homes marking the beginning of the real triumph of computer-aided manufacturing. Technology became increasingly available, powerful, user-friendly, and most importantly, more inclusive, thus turning people into information production machines.

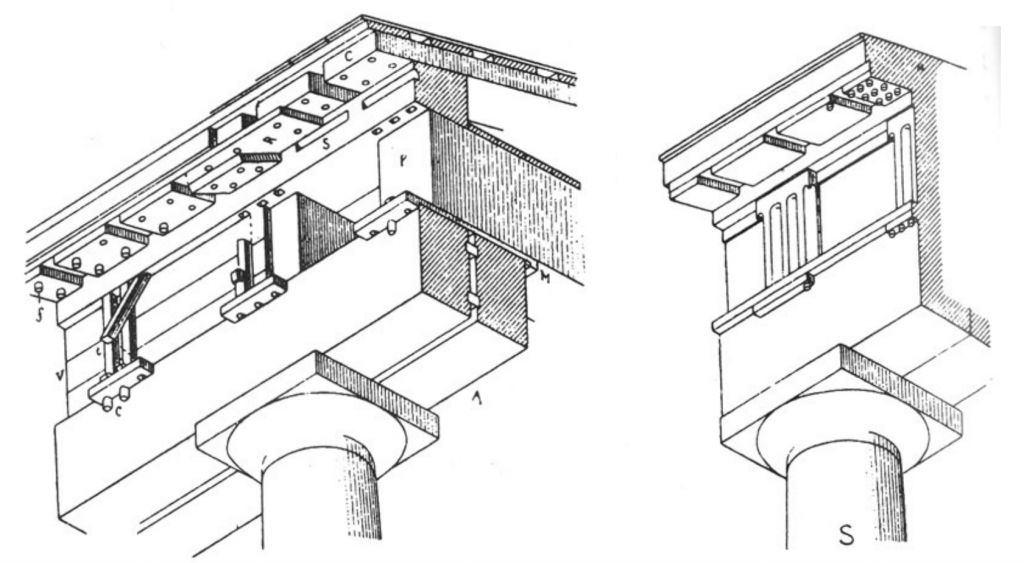

Francesco Borromini, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane main hall (left) the cuppola is a geometric masterpiece. The ceiling of the colonnade in the courtyard (right) reminds digitally savvy designers of subdivision geometry.

The early digital architects were largely influenced by Gilles Deleuze and his “The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque” . Leibniz as the alleged inventor of calculus was the hero of early digital architecture. Potential fields and monads perfectly resonated with digital architecture – rather than creating objects we build systems that allow us to instantiate an adapted object appropriate for the present situation.

The early digital architects also saw an opportunity here for taking the next step from deconstructivism. The form of an architectural object is indeed influenced by highly different and conflicting forces (not only physical but also historic, cultural, urban etc) but with calculus we can fold the given forces into a coherent system. This, in turn, allows us to combine topology and tectonics.

With regard to the realisation of such smooth forms, the question of geometry became once again an important issue. Classic and Baroque architecture came to be held in esteem again for their rigourous geometry. The study of the relations between geometry and construction were similarly given a new boost. It was clear that with the new tools, the given relations could be automated.

The triumph of early digital architecture lasted until the economic crisis in 2008, and during the crisis, digital architecture moved into laboratories. Design research got a boost and in addition to large technical universities such as ETH, industrial robots and 3D printers came to conquer increasingly more research institutions. The research in architectural design became both more technical and more experimental. They studied the qualities of various materials and the possibilities of machines, combining them in all imaginable ways (see the main exhibition of TAB

2015 “Body Building”).

Tallinn Architecture Biennale 2015 main exhibition Body Building

At about the same time, also parametric architecture took off, as scripting no longer required the writing of a complex code and the most widely used visual programming environment today – Grasshopper – emerged, allowing the stacking and joining of algorithms as needed. Panelisation was one of the tool’s first main functions, as the smooth surfaces were divided into producible elements – breaking the curve, as said by Mario Carpo. Parametric architecture came to be taken more seriously.

Digital architecture initially included a lot of post-rationalisation, i.e. making the so-called design surfaces constructible. This was done also by Frank O. Gehry who, in addition to his architecture office, established his own software company Gehry Technologies. They provided their software

The visual programming software Grasshopper enables the user to set up complex relationships between geometries. One of the main uses of the tool is surface panelisation.

and services to many well-known offices such as Zaha Hadid Architects, Coop Himmelb(l)au or UNStudio. At present, the company has been sold to Trimble, a huge corporation whose tag-line is „transforming the way the world works“, however, when I worked there as an intern in 2011, it was still a highly exciting and fast-growing company employing numerous people with their background in architecture. Ever since the two-month internship, I have firmly believed that the knowledge of architecture, engineering and manufacturing should be integrated in the design from the very beginning. With algorithmic means, it is possible to achieve the same kind of freedom in the creation of form as by the digital architects before the crisis, while also considering the constructional and geometric restrictions right from the outset. Furthermore, the given restrictions can be used creatively. This, in turn, marks an essential difference from the early digital architecture. If the latter was mostly concerned with the building surface that can be experienced, ignoring the construction, then the present methods allow the designer to regard the building as a comprehensive whole consisting of volumetric elements and consider their geometry as well as their structural and other physical qualities.

What for?

Thus we arrive at the present moment and I hope I have managed to provide a clear overview of what we have achieved in contemporary architecture and by which means. But now to the more difficult question, “What for?”

The present social mentality is not influenced merely by the fear of another economic crisis. The issue of climate change is considerably more important. It is further influenced by the political developments in recent years that are closely related with the fear of technological developments and issues of privacy. There is so much information available that people do not know what to make of it. Only computers can draw conclusions from big data using machine learning. Figuratively speaking, however, the results of machine learning would fail a basic school mathematics test as, on the one hand, they do indeed get the right answer, however, they do not write down the entire solution process. James Bridle calls the present era a New Dark Age. People have created such complex automated systems that it is impossible to comprehend the function of their every nuance.

The rise of conservatism is understandable in the given situation, however, it is an entirely useless tactic. Automation is too efficient to be stopped. The only way to influence the process is to become a part of it. A company like Trimble buying Gehry Technologies is a clear sign of where the construction sector is heading – complete digitalisation. The computational mindset is playing an increasingly important role in our life. The question is how people can remain human in such an automated dark age.

In his book “Ornament: The Politics of Architecture and Subjectivity”, Antoine Picon describes the three main functions of ornamentation – pleasure or decoration, politics or the organisation of social ranks, and the direct and indirect conveyance of knowledge. Ornament can thus tell a story or draw your attention to the building’s tectonic relations or the logic of its creation.

When considering the etymology of the word, ornament is derived from the word ordinare meaning to put in order. The aim of ornaments in the classic sense was to organise the elements of the building, to make them clearly readable and draw attention to them. Thus, the ornament is concerned with understanding and meaning. With interpreting the machinic world for people. When Loos declared the ornament a crime at the beginning of the previous century, the problem lay in the sprawl of industrially manufactured ornaments. One of the aims of Modernist architecture was to tackle the massive spread of poor design by means of minimalism. A hundred years later, minimalism has naturally acquired a number of additional meanings. On the one hand, minimalist Modernism has become a symbol of power and success, on the other hand, of inequality and inhumanity, “Only clean surfaces and conceit!”

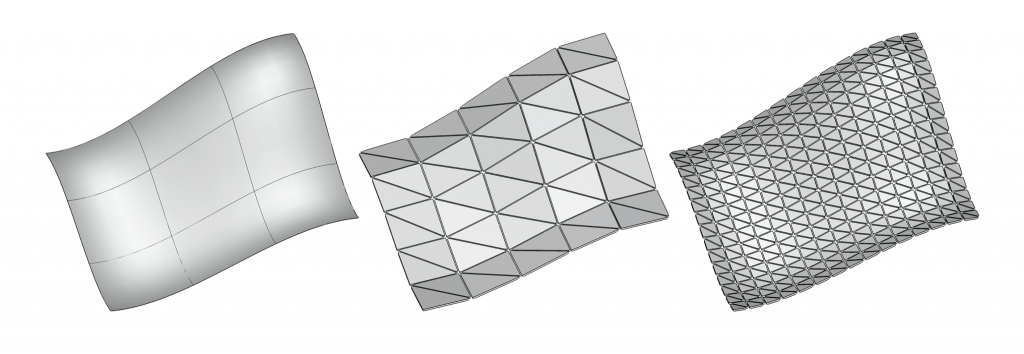

With the second digital turn, the ornament is reclaiming its classic roles, albeit obviously in a different form. Lately, there have been numerous young thinkers, who speak about both discrete and mereological (studying parts and the whole they form) architecture. It basically stands for design with elements (often with so-called element families) in which a limited number of various elements are combined to form a space that is more than a mere surface – it is a whole consisting of clearly differentiated parts. It is a readable system that is simple on the element level but at the same time allows for the creation of highly nuanced and complex forms (as well as very simple ones, of course). The mutual relations of the elements are limited – a result may be reached by combining them without any prior knowledge. Then again, the given simplicity can yield both chaos and order (see cellular automaton). The simplicity remains on the element level, while the whole is made as complex as the designer wishes. Its history, however, will not be concealed behind clear surfaces.

Cellular automata – repeating the simplest of rules can result in patterns of arder and chaos

The Digital Thicket series by PART architects is based on the given principle. It is basically a geometric system allowing the creation of particular free form structures out of one or several repeated elements. The given study began with the spatial identity of the opening ceremony of the Estonian EU Presidency. Digital or countable on fingers means that something consists of mathematically discrete parts, countable pieces. The Digital Thicket comprised of one repeated element with 750 logs manufactured on an automated milling machine. The milled geometry determined the way to join the elements. The structure could be, thus, put together without any prior knowledge as the elements can be joined in only one way. Like a gardener one can decide where the thicket could be allowed to burgeon and where it should be pruned.

Digital Thicket by PART Architects. The installation for the opening ceremony of the Estonian EU presidency carries the local nature loving and rapidly changing digital identity.

Here lies the main difference between the classic and contemporary ornament – the structure itself becomes the ornament. It is no longer a stucco or marble panel that can be removed. As there is such freedom in selecting the structural elements and details, the detail itself becomes an ornamental expression that reflects the author’s vision of the world that we inhabit. The selection of materials, joints, the form and tectonics of the building become a part of the communicative system.

The geometry of the Digital Thicket is by no means structurally optimal. It is basically a spring structure. However, this is what makes the structure ornamental. Its main aim is not to direct forces to the ground by the shortest route but to create human scale spaces. By means of algorithmic analysis, we can easily play gardener even on 20 metre high structures as is the case with the Urban Jungle installation that will soon arise in the T1 Mall of Tallinn. By using finite elements analysis, we have real-time information on how the structure behaves and where to add or remove elements. In my opinion, this is the ideal symbiosis of machine and human thinking.

Urban Jungle by PART Architects is an interior vertical garden of 18.5 metre height in the central atrium of T1 Mall of Tallinn opening at the end of October 2018.

As observed by Mario Carpo, there is no reason to think that artificial intelligence will replace man, there is no need for it. Human thinking is not the best way to comprehend the world – it is the only one that we have. Machines interpret the world one way – by means of big data. People do it by means of small data and the data compression algorithms inherent in us. We use words signifying a huge amount of information and changing their meaning pursuant to the situation, we use the decimal system as that is the number of our fingers etc. Machine thinking expands our opportunities, however, we must be able to interpret it back into human thinking and create a coherent world understandable to us. Yes, machines provide results, but why? The best we can do is to make the technology we have created work for us, not the other way round, and do it in a meaningful way. Coming back to Dennett, in evolution, things emerge without an aim, but they survive because they serve a purpose. They appear due to something but remain for something. As intelligent designers, it is our responsibility to attempt to answer the latter question.