Siim Tuksam

The theme of this year’s biennale “Fundamentals” is intriguing because in its precise definition it still allows for interpretation. Since Estonian architecture is greatly influenced by outside factors, the search for a distinctive national style was based on the mix of different styles typical for public spaces in Estonia. The aim of Interspace is to address contemporary architecture through the fundamentals of public space. Therefore, we decided to look at the development of the bastion area of Tallinn. It is the part of the city with the most important public functions and with most significance in terms of urban planning from the end of the Russian empire to the current day Republic of Estonia and beyond. In our study, we expose the different spatial and social changes that have accompanied each of the different regimes in this area, and consider how today’s networked data-society could continue to address public space.

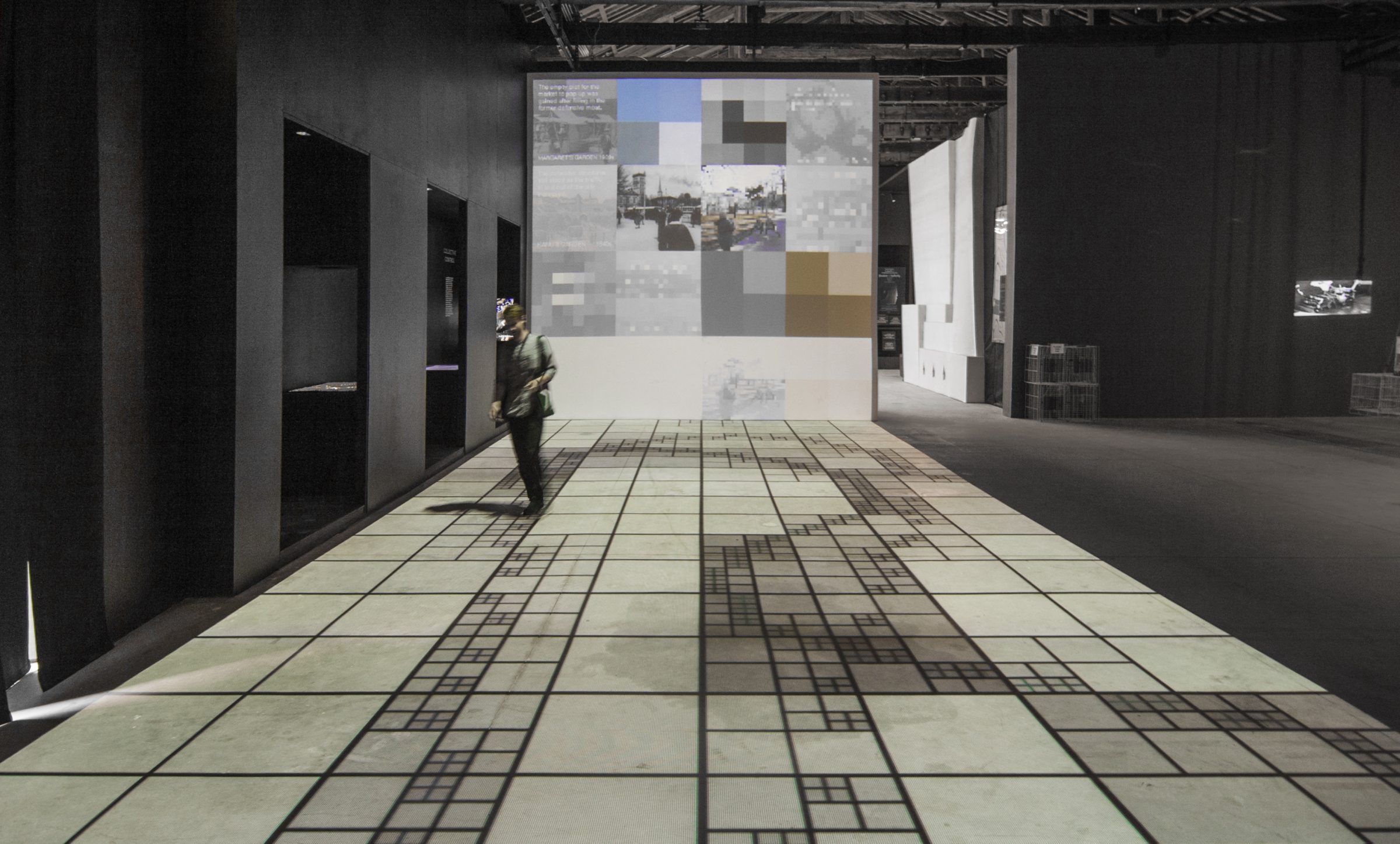

As an e-country, Estonia is an excellent example of a digitised society – not only open to new technologies and prepared for data-based functioning, but even encouraging it. It is believed that the key to a small nation’s success is a knowledge-based economy and automated and optimised social organisation. At least on the level of national discourse, a technology-based ideology dominates in Estonia. To provide a concept of how an e-country could use public space, the Estonian pavilion focuses on topics in contemporary architecture that are tied to technological development, such as data-based design and aesthetics, split agency, personalised readings and incorporating multitude.

Power and ideology

Power has often expressed itself through certain styles representing its ideology. Over the last 100 years Estonia has been under the rule of various occupiers and this is expressed in the urban landscape. The built environment has been rethought many times throughout history; various different statues and monuments have been erected and removed. The most significant embodiments of power are identifiable by their distinctive styles – probably the most dominant being Nevski Cathedral on Toompea. Its onion domes in the city skyline provided a clear message of who was in power. Whether the styles brought about by certain ideologies eventually also express these ideologies is doubtful. In the movie “The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology” Slavoj Žižek illustrates this with Beethoven’s Symphony No.9, which has been used by various ideological regimes from Nazi Germany to left-wing extremists in Peru. In his interview to Interspace Mark Foster Gage said, “Modernism was meant to be this mass-produced democratic thing, but it became a fetish for the elite”. Even though it seems paradoxical to talk about the development of style based on ideology, I believe that from a theoretical point of view the characteristics of the networked data-society indicate a certain style. Modernisation has been accompanied by a concept of idealistic generalisation – a metaphysical platonic ideal pure forms endeavour to achieve. This same idealist concept made it possible to use Modernism in different contexts, but was also the reason its promised democratic aspect failed. Today, we perceive with increasing clarity how complicated our society really is. Political crises of recent years show how impossible it is to subordinate diversity to an ideal system. Different images of what is happening in the world reach us through diverse information channels. During the Arab Spring social media was claimed to have helped justice to prevail, but it is increasingly clear that in one way or another all media is corrupt. The fantasy of an ideal metaphysical social order has been shattered. Instead we are putting our hopes on big data1 – data collected automatically in real time promises to show the world as it really is. We should not slip into idealist generalisations, but the analysis of enormous quantities of data seems to be the final promise for identifying patterns in chaos – without generalisation. Digital technology reaches everywhere. In commerce, it goes without saying that statistics are gathered about how much, where and why something is bought, and by analysing this data design, production and logistics are optimised. Nowadays all objects to which enough data collecting technology is attached, are linked to the internet of things. In this way, our environment and the people and objects moving within it have become agents in large computational models. Collectable data is limitless and increasingly influencing every aspect of our lives. We could say that data-based adaptability, diversity and variability have become the typical features of the ruling ideology.

Post-digital architecture

After a short fling with Postmodernism, the digital architecture of the early 1990s with its smooth, seamless surfaces, could be considered a return to modernist aesthetics. With the help of calculus it is possible to express Postmodernist ideas through ideal forms. Contradictory external “forces” were smoothly folded into mathematical surfaces. Spline constructed surfaces are defined by algorithms that interpolate smooth curves between sets of points. The appearance of cloud computation, the internet of things and big data are taking their place in digital Postmodernism, characterised by fragmentation, plurality and density. Mario Carpo elaborates on this big data style2 in this publication. The head curator of this year’s biennale Rem Koolhaas wrote about a similar tendency in Junkspace, “At the exact moment that our culture has abandoned repressive repetition and regularity as repressive, building materials have become more and more modular, unitary, and standardised; substance now comes predigitised […] Instead of trying to wrest order out of chaos, the picturesque is now wrested from the homogenised, the singular liberated from the standardised.”3 The ideological conflict here lies in the fact that attempts are made to build calculus based flowing forms from standard building materials. The logic of big data is based on the premise that nothing is infinitely seamless but on close inspection is always comprised of distinct parts. With the development of technology, architecture, over the last few years, has made increasing use of robotics. By using industrial robots some hope to achieve greater precision and capability, while others hope for greater integration between digital design and the end product. There are numerous different directions in this field. On one hand, robotic arms allow unprecedented precision, control and automation. ETH Zurich4 was one of the first universities where architects started experimenting with industrial robots for brick-laying – Gramazio;

Kohler’s Pike Loop represented Switzerland at the Venice Biennale in 2008. The other direction, mainly propagated by Greg Lynn, is kinetic architecture. Lynn has said, “If I can take a ride in a driverless car on a public street, then I see no reason why my building can’t wiggle a little”.5 In this context the neo-materialist direction of Marjan Colletti, also an author represented in this publication, might be the most interesting one. While Carpo’s big data style is characterised by fragmentation, neo-materialism is about making the most of material properties. Materials science is developing rapidly and it can be assumed that in the near future our building materials will become increasingly smarter. Robotic design is closing the gap between digital and physical production. This method makes it possible to overcome the problem of translation between the digital and the physical. To physically produce seamless computer generated surfaces today, they need to be divided into infinitely small parts – the resolution needs to be increased. 3D printers only recognise straight lines, meaning that in order to achieve continuity and to make the end result look similar to the actual design, it is necessary to calculate as many points as possible on a surface and then print as thin layers as possible. By exploiting material properties such as plasticity or flexibility, it becomes possible to create “pure forms” in the way a glassblower or sculptor does and, therefore, to abolish the issue of resolution. The material itself becomes a part of the digital model; tits properties become variables in the algorithm. Only time will tell whether such methods will ever find widespread practical application or not. Both directions provide an answer to the quote from “Junkspace”. Materials are generally not homogeneous, therefore also their inner logic is fragmented and uneven. Even though Colletti does not talk specifically about style, it could be said that neo-materialism produces big data style. Ideologically these two are every different though. Carpo talks about big data style as something which should be fragmented and composed of infinitely small parts. But the neo-materialistic point of view coincides with Koolhaas’ one: it should be possible to create order from chaos – to include the material properties into design thinking and thereby lose matter’s subordination to digital thinking.